ازسفر قهرمان به عنوان استعاره ای برای دگرگونی شخصی

سفر قهرمانی در دهمین کنفرانس بین المللی یادگیری دگرگون کننده: آینده ای برای زمین: بازسازی تصورمان از یادگیری برای ایجاد تحول در جهان: سان فرانسیسکو ، ایالات متحده آمریکا.

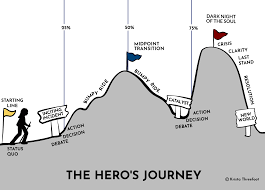

سفر قهرمان

بر اساس مبانی نظری روانشناسی یونگی و پژوهشهای گسترده در حوزه اسطورهشناسی، سفر قهرمانی، چارچوبی جامع برای درک فرآیند تحول شخصی ارائه میدهد. این سفر، با تاکید بر نقش محوری احساسات در تجربه تغییر، نشان میدهد که رشد فردی اغلب با چالشها و تنشهای جدی همراه است. از منظر این دیدگاه، هرچه فرد با موانع بزرگتری روبرو شود، فرصت بیشتری برای تحقق پتانسیلهای نهفته خود پیدا میکند. بازتاب انتقادی از خود، کلیدی است برای پیمودن این مسیر پر فراز و نشیب و دستیابی به رشد و دگرگونی پایدار.

این نوع از سفر ، با تأکید بر بازتاب انتقادی، چارچوبی برای درک این واقعیت ارائه میدهد که رشد شخصی فرایندی همراه با چالش و تنش است.

این سفر نشان میدهد که هرچه چالشها بزرگتر باشند، فرصت برای تحقق پتانسیلهای فردی بیشتر خواهد بود.

منابع غنی اسطوره ها

- داستانها، اسطورهها و افسانهها، به عنوان منابعی غنی برای درک ماهیت انسان، قرنهاست که مورد توجه قرار گرفتهاند.

- با در نظر گرفتن عمق روانشناختی و واقعگرایی احساسی این روایتها، میتوان از آنها برای تحلیل و درک فرآیندهای تحول شخصی بهره برد.

- هدف این مقاله، نشان دادن این است که با استفاده از ساختار اسطورهای سفر ، میتوان به درکی عمیقتر از این موضوع دست یافت که چالشها و تغییرات شخصی، نیروی محرکهای برای رشد و خودشناسی هستند.

- این پژوهش، با معرفی مفهوم “فراگیری”، رویکردی جامع برای درک فرآیند یادگیری تحولآفرین ارائه میدهد.

- با استفاده از استعاره سفر قهرمان، این پژوهش به بررسی فرآیند تحول شخصی و ارتباط آن با مفهوم فراگیر در یادگیری تحولآفرین میپردازد.

- دادههای جمعآوری شده در یک پژوهش ده ساله نشان میدهد که مدل سفر قهرمانی میتواند به دانشجویان در بیان تجربیات تحول شخصیشان کمک کند.

- نظریه یادگیری تحولآفرین، با توجه به تاریخچه پویا و تفسیرهای مختلف آن، ماهیت انعطافپذیر و سازگار با شرایط مختلف را نشان میدهد.

- در حالی که مفهوم سنتی یادگیری تحولآفرین، به رهبری مازیرو، بر تفکر انتقادی تاکید داشت، پژوهشهای بعدی ابعاد متنوعتری از این فرایند را مورد بررسی قرار دادند.

-

پژوهش ها

- این پژوهشها، دیدگاههای توسعهگرایانه (مانند کرانتون، دالوز و کیگان)، فراعقلانی (مانند بورد و دیرکس) و زیستمحیطی (مانند اوسالیوان) را برای درک جامعتر یادگیری تحولآفرین ارائه میدهند.

- با توجه به تنوع رویکردها در پژوهشهای یادگیری تحولآفرین، این مقاله با تلفیق ابعاد شناختی، تکاملی و فراعقلانی، یک مدل جامع برای درک این فرایند ارائه میدهد.

- این مدل، ضمن تأکید بر نقش محوری احساسات، بدون ادعای ارائه نظریهای کاملاً جدید، به بررسی ابعاد مختلف یادگیری تحولآفرین میپردازد.

- وولف (2006) و زول (2002) بر تأثیر متقابل احساسات و شناخت تاکید دارند. به گفته آنها، احساسات نه تنها بر آنچه میآموزیم بلکه بر نحوه تفکر ما نیز تأثیر میگذارند.

- این دیدگاه نشان میدهد که بروز احساسات، به ویژه احساسات منفی، میتواند نشانهای از تضادها و ابهاماتی باشد که در طول فرآیند تحول شخصی تجربه میشود.

-

دیدگاه تحول آفرین

- کرانتون با ارائه یک دیدگاه جامع، یادگیری تحولآفرین را فراتر از فرایندهای شناختی میداند و بر نقش احساسات، شهود و تجربیات غیرکلامی در این فرایند تاکید میکند.

- به گفته او، تغییرات عمیق شخصی میتواند به صورت ناگهانی یا تدریجی و به شیوههای غیرمنتظره رخ دهد.

- کرانتون، با معرفی مفهوم رویدادهای برهم زننده و تردید در باورهای قبلی، دو مرحله اولیه یادگیری تحولآفرین را ترسیم میکند.

- وی همچنین بر اهمیت گفتگو و تعامل اجتماعی در این فرایند تاکید دارد.

- دیریکس با اشاره به پیچیدگی و بی نظمی فرایند خودشناسی، بر اهمیت ادغام آگاهانه ابعاد عاطفی و معنوی در زندگی روزمره تاکید میکند.

او پیشنهاد می کند که پرورش روح “تلاشی برای پذیرش آشفتگی و بی نظمی در یادگیری های دوران بزرگسالی است” (Dirkx، 1997 ، ص 84) تا با استفاده از داستان ، آهنگ ، اسطوره ، شعر و تجربیات روزمره روح را تغذیه کند ، و به فرد کمک کند تا با احساسات و عواطف خود درباره روابطش با جهان گسترده تربیرون بیاموزد (Dirkx، 1997، p. 83). داستان ها ، اسطوره ها ، افسانه ها و آثار کلاسیک ابزاری برای دگرگونی هستند که در تکرار آزمون ها و مصائبی که ما به عنوان بخشی از درک انسان بودن خود تجربه می کنیم ، می توانند به زندگی ما معنا ببخشند.

جوزف کمبپل

جوزف کمبل در پژوهشهای گستردهاش بر روی اسطورههای قهرمانی سراسر جهان، به این نتیجه رسید که تمامی این روایتها، فارغ از فرهنگ و زمانه، از ساختاری واحد و مراحل مشترکی پیروی میکنند. او این ساختار مشترک را سفر قهرمان نامید و معتقد بود که این سفر، نمادی از تحول درونی انسان و جستجوی معنا در زندگی است. کمبل بر این باور بود که ناخودآگاه جمعی بشر، الگوهای اسطورهای را در همه فرهنگها تکرار میکند و این الگوها، ریشه در اعماق روان انسان دارند. وی با تمرکز بر درک زندگی و خودشناسی، تغییرات و چالشهای زندگی را نه مانعی، بلکه فرصتی برای رشد و تحول میدانست.

کمپل طی پژوهشهای گستردهاش، مراحل مختلفی را در اسطورهها شناسایی کرد که میتوان آنها را در رویدادهای زندگی روزمره نیز مشاهده نمود. این مراحل، لزوماً به صورت خطی و متوالی رخ نمیدهند، اما شباهتهای قابل توجهی بین آنها و روایتهای اسطورهای وجود دارد. کریستوفر وگلر، فیلمنامهنویس هالیوودی، با الهام از نظریات کمبل، دوازده مرحله مشخص برای “سفر قهرمان” ارائه کرد که نشاندهنده تحول و رشد شخصیت است.

- جهان معمولی 2. دعوت به سفر 3. رد دعوت 4. ملاقات با مربی 5. عبور از آستانه اول 6. آزمایش ها ، متحدان و دشمنان 7. رویکرد به درونی ترین غار (آستانه دوم) 8. مصیبت اعظم 9. پاداش (گرفتن شمشیر) 10. راه برگشت 11. رستاخیز 12. بازگشت با اکسیر (آزادی برای زندگی).

سفر

بنابراین ، مفهوم یادگیری تحول آفرین که مناسب سفر قهرمانی است ، تفسیری است که تفسیرهای شناختی-عقلانی ، ساختارگرا – تکاملی و فراعقلانی نظریه یادگیری تحول آفرین را ترکیب می کند. مفهومی که شامل این موارد می شود ، به دنبال تجربیات شخصی سرگردان ، در هم ریخته و دارای بار احساسی است که در هنگام مواجهه نگرش جدید با شیوه های قدیمی شناخت برانگیخته می شوند و هستی فرد را به چالش می کشند و او را به سوی فضایی ناشناخته می برند.

این “فضا” غالباً با سردرگمی ، عدم قطعیت و چالش مشخص می شود ، زیرا رهرو/فرد فراگیراز منطقه امن و شناخته شده خود خارج می شود ، از اولین آستانه عبور می کند و در حالی که برای “از یاد بردن” عادات قدیمی به چالش کشیده می شود ، با آزمون هایی روبرو می شود. قبل از اینکه رهرو بتواند آینده را بازسازی کند ، باید گذشته را از هم باز کند/تجزیه کند ، اما با رسیدن به آینده ، می توان گفت که یادگیری واقعاً دگرگون کننده بوده است.

استفاده از چارچوب سفر قهرمانی

دانشجویان بزرگسال برنامه STEPS در دانشگاه CQU استرالیا، اغلب با چالشهای یادگیری در محیط دانشگاهی مواجه میشوند. این افراد که از دنیای کار با تجربیات پیشین به دانشگاه آمدهاند، نیازمند حمایت و راهنمایی برای سازگاری با روشهای آموزشی جدید و مفاهیم پیچیده آکادمیک هستند.

بسیاری از آنها تجربیات قبلی منفی خود از سیستم مدرسه را منتقل می کنند ، بنابراین STEPS سعی می کند سیستم اعتقادی آنها را نه تنها در مورد خودشان به عنوان یادگیرنده بلکه در مورد خود یادگیری نیز به چالش بکشد و گسترش دهد. به طور معمول ، اکثر دانش جویان از شرایط اجتماعی و اقتصادی پایین برخوردار هستند و اولین کسانی در خانواده هستند که به دانشگاه می روند.

بیشتر دانشجویان در بازه سنی 18 تا 65 سال هستند و در ضمن اینکه که 12 یا 24 هفته برنامه دانشگاهی یا از راه دور STEPS را مطالعه می کنند مشغول کار پاره وقت هستند و اکثریت آنها تعهدات و مسئولیت های خانوادگی قابل توجهی دارند. مدتهاست که STEPS از بینش سفر قهرمانی حمایت می کند چرا که این دیدگاه به عنوان ابزاری قدرتمند برای بازتاب خود کمک می کند تا به دانش جویان بفهماند که اگرچه سفر یادگیری رسمی آنها در بسیاری از سطوح دشوار است ، اما طی کردن این سفر درونی و بیرونی می تواند منجر به رشد و دگرگونی شخصی قابل توجهی شود.

سفر دانشجویان

دانشجویان به طور جدی تشویق می شوند تا با استفاده از دفتر یادداشت های شخصی احساسات خود را ثبت کرده و نقد کنند ، به خصوص زمانی که مفروضات طولانی مدت آنها درباره خودشان و جهان به چالش کشیده می شود. چنین خوداندیشی می تواند محرکی قدرتمند در تجزیه و تحلیل مفروضات قبلی باشد که ممکن است مانع رشد آنها شده باشد . بسیاری از جویان با تأمل در پاسخ به مشکلات شخصی ، خودآگاهی و خودشناسی قابل توجهی را تجربه می کنند.

دانشجویان برنامه STEPS، داستانهای شخصی خود را از گذر از یک زندگی روزمره به یک ماجراجویی یادگیری به اشتراک میگذارند. این داستانها، شباهتهای بسیاری با ساختار کلاسیک سفر قهرمان دارند. بسیاری از دانشجویان بیان میکنند که احساس نارضایتی از زندگی قبلی خود، آنها را به سمت جستجوی یک تغییر اساسی سوق داده است. این نارضایتی، همانند فراخوانی برای آغاز یک سفر، آنها را به دنیای جدیدی از یادگیری و کشف خود وارد کرده است.”

تجربیات دنیای قدیمی

به قول یکی از دانش جویان ، “دنیای قدیمی من مملو از تجربیات ناخوشایند شغلی و این احساس بود که می توانم دستاوردهای بیشتری داشته باشم- که ارزش من بسیار بیشتر است. از دست دادن شغلم سخت بود اما من را مجبور کرد به دنبال چیز جدیدی باشم. من توسط نیروهای خودسازی جذب شده بودم “. برای سایر دانش جویان ، دعوت به سفر ممکن است اشتیاقی طولانی تر برای برآوردن آرزوهای برآورده نشده باشد ، مانند دانش جویی که برای مدت طولانی بیکار بوده است.

همانطور که او گفت: “حتی این که از رختخواب بیرون بیایم برایم یک چالش محسوب می شد. می دانستم که باید کاری انجام دهم … مسیر شغلی ام را تغییر دهم، با ترس هایم روبرو شوم و احساس ناقصی که همیشه داشتم را رفع کنم. ” رد دعوت برای دانشجویان STEPS اشکال مختلفی دارد و اغلب با ترس از تغییر یا رشد مرتبط است. شواهدی از حکایت های آنها در ده سال گذشته نشان می دهد که چنین ترسی می تواند مربوط به “به خطر انداختن زندگی خصوصی و عمومی آنها باشد”.

نکته مهم

سایر دانش جویان ترس از ناامید کردن خود و خانواده را بیان می کنند ، یا در مورد نحوه تعدیل نقش های متعدد زندگی تردید دارند. با این حال ، هنگامی که دانش جویان موانع پیش روی خود را مورد انتقاد قرار می دهند ، بسیاری از آنها می بینند که چگونه شیوه های تفکر قدیمی، رشد آنها را محدود کرده است. همانطور که یکی از دانش جویان می گوید: “من فکر می کردم که من خیلی پیرشده ام و باید دیوانه باشم که در این برهه از زندگی ام تغییرات بزرگی را عملی کنم” ، در حالی که دلیل یکی دیگر از دانش جویان برای رد دعوت، صدایی در سر اوبود که می گفت: “تو زیادی احمقی”.

با این حال ، یکی از دانش جویان بیان کرد که چگونه تأمل درباره رد دعوت به تجسم امکان های جدید کمک کرده است: “احساسات شک و تردید سرم را پر کرده بود و می پرسیدم آیا مغز درون سرم هنوز هم واقعاً کار می کند یا نه ، اما من متوجه شدم که تنها چیزی که قرار است به من کمک کند چرخه زندگی سخت خود را متوقف کنم ، خودم هستم. ” در داستانها و اسطوره ها ، مربی/راهنما معمولاً شخص خردمندی است که قهرمان را در چالش خود هدایت می کند. برای دانش آموزان STEPS ، ملاقات با مربی معمولاً شامل یک عضو خانواده یا دوست است ، یا شاید تجربه ای که چیزی را در آنها بیدار می کند تا متوجه شوند که معنای بیشتری برای زندگی وجود دارد.

الهام بخشی

اغلب، استادان STEPS مربی می شوند یا دانش آموزان در بین همکلاسی های خود مربی می یابند. همچنین ، افراد الهام بخش می توانند به عنوان مربی عمل کنند ، که توسط یکی از دانش آموزان بیان شده است: “مربیان من مادر ترزا ، گاندی ، مارتین و دزموند بودند ، همه با هم روی جلد دفتر یادداشتم. آنها هر روز در کیفم با من می آمدند و آنجا بودند تا با آنها صحبت کنم ، احساس کنم. ” برخی از دانش آموزان حتی در درون خود برای یافتن مربی تمرکز می کنند ، که توسط یکی از دانش آموزان بیان شده است: “مربی من واقعاً خودم هستم. من می خواستم با زندگی ام کاری متفاوت انجام دهم و می دانستم که می توانم آن را انجام دهم. ”

مواجهه با اولین مشکل و برخورد با آن نشان دهنده مرحله ای است که دانش آموزان STEPS از آستانه اول عبور می کنند. برای برخی ، ممکن است این شرکت در اولین روز STEPS باشد، به قول یکی از دانشجویان: “ورود به کلاس در روز اول ، در حالی که همه یکدیگر را بررسی می کردند و قضاوت می کردند بسیار دلهره آور بود”. برای دیگران ، اولین آستانه ممکن است ارائه یک کار یا آزمون ارزیابی باشد ، یا اضطراب برای صحبت در مقابل کلاس که شجاعت آنها را آزمایش می کند. گاهی اوقات این مشکل ممکن است ماهیت شناختی داشته باشد ، مانند تلاش برای درک یک مفهوم ریاضی جدید یا نداشتن هیچ ایده ای برای نوشتن.

عبور از آستانه

برای برخی از دانشجویان ، عبور از آستانه اول می تواند بسیار احساسی و شخصی باشد ، مانند پایان دادن به یک رابطه یا دوستی به دلیل تضاد آرزوها. همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان پسر می گوید: “متأسفانه رئیس من ورود به دانشگاه را ایده خوبی نمی دانست و وقتی من تحصیل را به کار ترجیح دادم آن را یک توهین شخصی قلمداد کرد. ما دچار اختلاف شدیم و از هم جدا شدیم ، دیگر اصلا صحبت نمی کنیم. ” دانش آموزان STEPS معمولاً در تلاش خود با آزمون ها ، متحدان و دشمنان زیادی روبرو می شوند. بسیاری از دانش آموزان درآمد کم را بزرگترین آزمون خود می دانند ، در حالی که تأخیر در انجام وظایف می تواند برای برخی دیگر دشمن مهمی باشد.

همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان گفت: “تعلل همیشه بدترین دشمن من بوده است. اگر کاری را شروع نکنم ، پس شکست نمی خورم و در نتیجه کسی نمی تواند مسخره ام کنم. ” برای دیگران ، شک و تردید به خود یک چالش مهم است که توسط یکی از دانشجویان بیان شده است: “بزرگترین دشمن من در این سفر خودم بودم زیرا باور نداشتم که می توانم رویای خود را محقق کنم”. دشمنان حتی می توانند به شکل چالش های فنی ظاهر شوند، مانند دانشجویی که به طور استعاری از کامپیوتر خراب شده خود به عنوان “دشمن اصلی” خود یاد می کند.

متحدان

از دیدگاه احساسی ، دشمنان می توانند احساس گناه به دلیل کاهش زمان بودن با عزیزان ، یا حسادت ابراز شده توسط دوستان یا شرکا باشند. از طرف دیگر ، متحدان می توانند افراد ، افکار ، تکنیک ها و استراتژی هایی باشند که به فرد رهرو در مسیر خود کمک کرده اند. نیروی درونی متحد دیگری برای برخی از دانشجویان است که توسط یکی از آنها بیان می شود: “خیلی وقتها من فقط دلم می خواست تسلیم شوم اما می دانستم این به من کمک نخواهد کرد ، بنابراین با پشتکار به راه خود ادامه می دادم”.

بالا رفتن خودآگاهی نیز می تواند یک متحد باشد ، همانطور که توسط یکی از دانشجویان بیان شده است: “با گذشت زمان در STEPS ، احساس کردم که می توانم ذهنم را باز کنم و به تدریج درک من از نحوه نگاهم به زندگی و جهان به طور کلی در جهت بهتر شدن خودم تغییر کرد”. با ادامه سفر STEPS ، چالش های بیشتری برای مواجه شدن وجود دارد و بسیاری از دانشجویان به آستانه دوم یا غار درونی نزدیک می شوند. چنین چالش هایی ممکن است مربوط به شخص دیگری باشد ، یا شرایطی که باید بر آن غلبه کرد ، یا یک مانع درونی که پیشرفت را محدود می کند ، مانند گفتگوی منفی با خود.

مقاومت

برای برخی از دانشجویان ، یک چالش مهم می تواند برخورد با مقاومت اعضای خانواده باشد ، که توسط یکی از دانشجویان بیان شده است: “خانواده ام با من مخالف هستند! من اکنون در خانه ایستاده ام و می گویم ، هی! ، من دیگر این وضعیت را تحمل نمی کنم و اکنون نوبت زندگی من است “. سایر دانشجویان با چالش های مربوط به تنش در بین اعضای کلاس روبرو می شوند ، که گاهی اوقات در سطوح بالای استرس افزایش می یابد

همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان می گوید: “حضور در کلاس با بزرگسالان ، در حالی که همه در مورد خود شک دارند و همه جا پر از احساسات استرس زا است دشوار است … برای من حضور در یک محیط پرخاشگرانه و مخرب سخت بود … خدا را شکر که ما یک هفته تعطیلی داشتیم … واقعا به آن نیاز داشتم! ” مصیبت اعظم تاریک ترین لحظه قهرمان است که ممکن است اعتماد به نفس از بین برود و همه چیز تیره و تار به نظر برسد ، با این حال قهرمان می تواند در برابر اضطراب و شبهات ظاهراً طاقت فرسا ایستادگی کند. برای دانشجویان STEPS ، این سخت ترین چالش است ، لحظه ای که بخشی از خود رها می شود ، مانند یک رفتار خاص ، مقاومت ، طرز فکر قدیمی یا حتی یک رابطه.

تکالیف تحقیقاتی

برای برخی ، این مصیبت بزرگ ممکن است ماهیتی شناختی داشته باشد ، مانند آنچه که توسط یکی از دانشجویان بیان شده است: «بزرگترین مصیبت برای من ، تکالیف تحقیقاتی بود … اشک ریختن در حال نوشتن احساسات متفاوتی از خودم در من ایجاد کرد ، واقعا از پس کارها بر می آیم؟ ” برای سایر دانش آموزان ، این سختی بزرگ می تواند ماهیت شخصی داشته باشد ، مانند کسی که می گوید: “من چهار هفته به شدت بیمار بودم و هر روز فقط برای بلند شدن از رختخواب تلاش می کردم. من به ترک کردن درس و کلاس بسیار نزدیک بودم زیرا برایم بسیار سخت بود که تمرکز کنم و در مسیر خود قرار بگیرم. ”

برای برخی ، این سختی بزرگ می تواند فشارهای رابطه ای باشد ، همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان می گفت: “رابطه من با دوست دخترم دو روز قبل از امتحان ریاضی من پایان یافت … من فکر می کردم دنیای من به پایان رسیده است و بدون او نمی توانم ادامه دهم. اما من فقط دندان هایم را به هم فشردم و تصمیم گرفتم ادامه دهم. ” هنگامی که قهرمان پاداش می گیرد و شمشیر را می یابد ، دیدگاه های خاص وی در مورد خود و دیگران تغییر می کند و قدرت درونی در او تحقق می یابد. بسیاری از دانشجویان STEPS از نظر عاطفی قوی تر شده اند و در مقابله با شکست ها مقاوم تر هستند. همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان گفت: “اکنون که به چالش های پیش روی خودم نگاه می کنم ، به خودم افتخار می کنم که تسلیم نشدم و سرانجام کاری را که شروع کردم به پایان رساندم”.

راهی برای پیروزی

فرد دیگری در مورد بینش شخصی پیشرفته ای که تجربه کرد گفت: “پاداش من این بود که ببینم آنقدر بسته نیستم که هیچ راهی برای پیروزی بر ترس هایم وجود نداشته باشد. من به چیز بسیار مهمی برای خودم دست یافتم “. پاداش برای دیگر افراد می تواند به شکل بالا رفتن سطح خودشناسی باشد ، همانطور که توسط دانشجویی بیان شده است: “من بسیار سرسخت و با پشتکار هستم ، اما به این نتیجه رسیده ام که شما باید راههای قدیمی را رها کنید تا جا برای پذیرش ایده ها و چالش های جدید داشته باشید. “.

قهرمان مجهز به نیروی درونی جدید ، راه بازگشت را می پیماید و با عواقب رویارویی با ترس های مصیبت بزرگ خود روبرو می شود. بسیاری از دانشجویان از خودِ قبلی خود فراتر رفته اند و می دانند که خود جدیدشان چقدر می تواند توانمند باشد. همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان گفت: “STEPS من را تغییر داده است. اکنون احساس می کنم می توانم مدرک دانشگاهی بگیرم و به بهترین نتیجه ممکن دست پیدا کنم – و من مشتاقانه منتظر این چالش هستم. ” یکی دیگر از دانش جویان گفت: “من احساس می کنم بعد از تجربه STEPS قوی تر و شادتر هستم.

پایان سفر

من می دانم که اکنون می توانم به هر چیزی دست پیدا کنم و این فقط محدود به خواست خودم هست ، نه هیچ کس دیگر. ” بسیاری از دانشجویان درباره آینده جدید صحبت می کنند ، مانند کسی که می گوید: “سفر به پایان رسیده است … ذهن من کار زیادی کرده و بدن من باید بخوابد ، اما من بسیار خوشحالم. زندگی من به حالت قبل باز می گردد اما با یک جهت جدید ، زیرا من یک فرد جدید با دیدگاه های متفاوت نسبت به مردم و زندگی هستم. ” در پایان STEPS ، بسیاری از دانشجویان تعهد خود را نسبت به تغییر شخصی و کنار گذاشتن شیوه های قدیمی تفکر و رفتار نشان می دهند.

رستاخیز با درک طیف وسیع تری از گزینه ها و جهان گسترده تری برای فتح کردن به دست می آید. به طور عمده ، دانشجویان STEPS از افزایش اعتماد به نفس و عزت نفس ، الهام و انگیزه ای که به دست آورده اند و تصمیم برای ایجاد تغییر در جهان خود صحبت می کنند. همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان اعلام کرد: “من می خواهم جهان را تغییر دهم ، آن را تقویت کنم ، آن را در آغوش بگیرم” ، در حالی که دیگری در سفر یادگیری بعدی خود تأمل کرد و گفت: “سفر من به پایان نرسیده است … با تجربیات و دانش جدیدم ، باید ادامه دهم،

آدم های گم شده

من می خواهم به دیگرانی مانند خودم کمک کنم … آدم های گم شده. اگر بتوانم تنها به یک نفر دیگر کمک کنم آنچه من هم اکنون احساس می کنم را احساس کند ، کاملا ارزش همه سختی ها را خواهد داشت. ” در آخرین مرحله از سفر قهرمان ، بازگشت با اکسیر (آزادی برای زندگی) است. دانشجویان STEPS که متحول شده اند ، پس از انجام موفقیت آمیز آنچه که برای دستیابی به آن تلاش کرده بودند ، به دنیای عادی خود باز می گردند. مسلح به دانش ، مهارت و اعتماد به نفس جدید. دیگر بازگشت به شخصی که قبلاً بودند در کار نیست. با وجود فداکاری ها و تلاش ها برای تبدیل شدن به شخص جدید ، آنها اکنون مسئولیت پذیرترهستند و ذهن بازتری دارند.

همانطور که یکی از دانشجویان تأملات خود را بازگو می کرد : “من هرگز نمی توانم به عقب برگردم – زنی که به چای خیره می شد و دنیا را تماشا می کرد ، رفته است. او اکنون داستان جدیدی دارد “. دانشجوی دیگری نیز به طور مشابه بیان کرد و گفت: “تکمیل دوره STEPS من را به سمت بهترشدن تغییر داد. من خود قدیمی ام را پشت سر گذاشته ام و خود بهتری را ابداع کرده ام”. برای برخی ، اکسیر عشق یا امید و انتظار است و برای برخی دیگر حکمت است ، مانند یکی از دانشجویان که در این باره گفت: «آیا وقتی دروازه یادگیری باز می شود آیا می توان به دنیای معمولی باز گشت؟ همه چیز بسیار دور و پیش پا افتاده به نظر می رسد. ”

نتیجه گیری

سفر قهرمانی یک چارچوب بسیار مفید برای توضیح چند بعدی بودن تغییرات زندگی شخصی ارائه می دهد. بر اساس یک مفهوم فراگیر از یادگیری تحول آفرین که عناصر شناختی ، تکاملی و فرا عقلانی را ترکیب می کند ، سفر قهرمانی جلوه های احساسی را قادر می سازد تا خویشتن درونی را منعکس کنند. زمانی که مفروضات قدیمی شخص شناسایی و شکسته می شوند ، می توان دوره های ترید ، هرج و مرج و تنش را انتظار داشت. با این حال ، شناخت چنین چالش هایی به عنوان نقطه آغازین مهم برای تغییر و رشد شخصی به حساب می آیند، و درک اینکه به طور کلی قدرت و تاب آوری چنین لحظاتی تولد یک فرد جدید با خودشناسی و خودآگاهی جدید را در پی خواهند داشت ، می تواند بسیار رهایی بخش باشد.